When the 20-year-old Felix Mendelssohn conducted Bach’s Saint Matthew Passion in Berlin in 1829, it caused a national sensation. In those days, when a composer died his contemporaries stopped playing him and his music died as well. But Mendelssohn, a brilliant composer, pianist and conductor who felt indebted to Bach, broke with tradition and performed the work for an audience that included the philosopher Hegel, the King of Prussia and the poet Heinrich Heine. It was the first time the piece had been played since Bach’s death in 1750, and it ignited an era of rediscovery that turned the baroque composer back into a household name. Without Mendelssohn, the Nazis might never have embraced Bach a century later as an exemplary Aryan composer, calling him “the most German of all Germans.” But in a cruel twist of history, Mendelssohn’s role in rescuing Bach didn’t stop the Third Reich from banning his works and destroying his legacy because he was a Jew.

Jewish issues

Designer of new World Trade Centre to build synagogue in Munich

Notorious for its lingering sentiments about the Nazi years, Munich has been mixed up before in controversies involving Jewish remembrance, such as Mayor Christian Ude’s refusal in 2004 to allow the brass-plated Stolpersteine, or Stumbling Stones, to be installed in streets as individual memorials to Jews killed in the Holocaust. This time, members of Munich’s … Read more

A New Context for the Holocaust

With far-right anti-immigrant parties strengthening in Austria, and growing opposition to the mosques and minarets shooting up from Berlin to Cologne, xenophobia is in the air in Europe. Pending job losses from the financial fallout may soon make matters worse. That’s why, when violinist Daniel Hope got the idea of hosting a 70th anniversary concert for Kristallnacht in Berlin, he wanted it to be more than a remembrance of the Holocaust and World War II. “It’s also about now, about violence against foreigners and any kind of racism,” he said. “We’re at a time, in an unstable atmosphere, where we can’t afford to be looking away and watching again.”

Tours follow Sephardic Routes

For Aida Oceransky, life as a Jew in Spain today isn’t the silent burden it used to be. When she emigrated to Asturias from her native Mexico in 1968, Oceransky didn’t dare talk about her family’s Ukrainian Jewish past. All the Jews she knew in the 1970s and ’80s went to Mass. Even a decade ago, “you couldn’t find anything on Judaism in Spain—a magazine, a book, nothing,” she said.

Gerhard Buck

Gerhard Buck’s earliest memory occurred when he was two years old and his parents took him to see the town synagogue burning. He can still recall the leaping flames and the “certain idea of destruction” that Kristallnacht imprinted on his mind. Adding to the trauma is Buck’s life-long doubt as to whether his own mother, when the Nazis came to her door asking for help, provided matches used to set fire to the building.

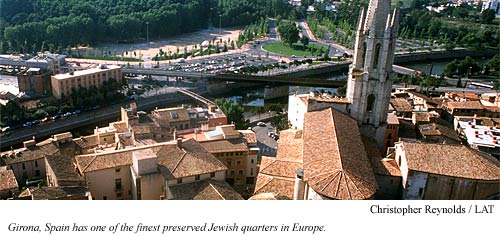

With Sephardic Routes, Spain Connects with Jewish History

GIRONA, Spain—For Aida Oceransky, life as a Jew in Spain today isn’t the silent burden it used to be. When she emigrated here from her native Mexico in 1968, Oceransky didn’t dare talk about her family’s Ukrainian Jewish past. All the Jews she knew in the 1970s and ’80s went to Mass. Even a decade ago, “you couldn’t find anything on Judaism in Spain – a magazine, a book, nothing,” she said.

Historic Revival

Once haunted by memories of the Holocaust, Berlin has become one of the most Jewish-friendly places on the planet. The German capital boasts an annual Jewish film festival and Jewish culture festival, while performances of Jewish plays attract regular audiences at the Bamah Jewish Theater. Visitors can view exhibits on emigration at the Jewish Museum; the music-minded can take in klezmer concerts performed by the Berlin Philharmonic.

Jonathan Safran Foer To Release English Version of Haggadah

Jonathan Safran Foer will be releasing a new English version of the Passover Haggadah, the best-selling novelist recently confirmed, speaking to a packed German audience at the American Academy in Berlin’s lakeside villa on the outskirts of the capital.

Wilfried Weinke

The two aims driving Wilfried Weinke’s work as a historian are, on the one hand, to confront a young, mainstream German public with the Holocaust in ways that bring the country’s former Jewish legacy to life, and, on the other hand, to rescue the names of forgotten German Jewish artists and intellectuals from the past. As J. Joseph Lowenberg, the grandson of the early 20th century poet Jakob Loewenberg, said, “Without Weinke’s efforts, I doubt that my grandfather’s literary reputation would receive any recognition in Germany today.”

ERNST SCHÄLL

Every day except on Sundays, for more than 20 years, Ernst Schäll, a retired mechanic, would wake up, step out his door and go to the Jewish Cemetery in Laupheim where his workshop, filled with tools and the crumbling parts of tombstones, awaited him. There he would set to work, grinding and drilling, repairing and rebuilding, sculpting each stone with 30 to 70 hours of labor before he replanted it on the grave where it belonged. According to those who watched and sometimes participated with him, Schäll brought more than technical skill and an artist’s instinct to his voluntary work restoring graves.