GIRONA, Spain—For Aida Oceransky, life as a Jew in Spain today isn’t the silent burden it used to be. When she emigrated here from her native Mexico in 1968, Oceransky didn’t dare talk about her family’s Ukrainian Jewish past. All the Jews she knew in the 1970s and ’80s went to Mass. Even a decade ago, “you couldn’t find anything on Judaism in Spain – a magazine, a book, nothing,” she said.

Now, more than five centuries after Spain violently expelled its Jews, the country is experiencing a revival of interest in Sephardic heritage – and neither Oceransky nor the 40,000 other Jews living here feel as though they have to whisper about their identity.

In fact, Sephardic culture has seen a boom in Spain in recent years. There’s Noah Gordon’s international bestseller, “The Last Jew” (set during the Spanish Inquisition), and the 2004 Spanish comedy “Only Human”, as well as conferences, music festivals, and even restaurants specializing in Sephardic cuisine. The biggest splash is the government-sponsored initiative known as Caminos de Sefarad, or Sephardic Routes, a network linking 15 medieval Jewish cities across Spain on the first-ever travel itinerary through the diaspora in Spain.

Unlike Berlin and Prague, Czech Republic, and other European cities where a lost Jewish heritage has been a cultural steppingstone for years – and where old Jewish quarters, synagogues and cemeteries are almost mandatory tourist stops – the curiosity in Spain’s Jewish sites has grown up almost overnight.

A growing number of tourists is coming to Segovia, a city in Spain’s Castile region, not only to see its towering Roman aqueduct but also to get a glimpse of a rediscovered Jewish past. “People want to see the Jewish quarter because it’s practically unknown – and because they don’t expect it,” said Marta Rueda, a guide who once led former Israeli Prime Minister Shimon Peres on a tour through Segovia’s old streets.

Granted, the Jewish cemetery stands on an unmarked hill opposite the town; the old synagogue has been turned into Corpus Christi Church; and about 100 Jewish homes were leveled centuries ago to make way for a vast Gothic cathedral. Nowadays, the most notable Jewish features of Segovia are its modern eateries, such as the Menora Café and El Fogón Sefardà restaurant. Nonetheless, the mere investigation of its Jewish legacy “is something new.”

“Even people from Segovia never learned about the Jewish quarter,” Rueda said. “Now people want to know their history.”

Spain’s relationship with its Sephardic legacy has in many ways been a centuries-long struggle against silence. In the Middle Ages, Jews played a major role in the country’s success – as astronomers, doctors, merchants and aides to the Catholic monarchy – until King Ferdinand exiled them and the Muslims with the expulsion edict of 1492.

In the 19th century, Jewish merchants started to trickle back in from Greece, Germany and elsewhere in Europe. They built the first modern synagogue in Madrid in 1916 and many fought on the side of the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War, which ended with Gen. Francisco Franco taking Fascist control of the country in 1939.

Decades of religious oppression forced the community into the background. It wasn’t until 1968, after laws had loosened, that the Spanish council of Jewish communities emerged, giving shape to the new community.

In more recent years emigration from Morocco and Latin America increased Spain’s Jewish population to about 40,000. In 1992, Franco’s successor, King Juan Carlos I, addressing members of a Madrid synagogue on the 500th anniversary of the Inquisition, formally welcomed the “return home” of Jews to Spain. Since then, Jewish culture, history and identity – like those aspects now visibly promoted on the Sephardic Routes – have enjoyed an almost reinvented status.

“Everything remained unrecognized about the Jews for so many years,” said Ana MarÃa López, director of the Sephardic Museum in the artist El Greco’s famed city of Toledo. The museum is adjoined to El Tránsito Synagogue, a masterpiece of 14th century architecture with ornate rafters and biblical wall inscriptions. Visits to the synagogue and museum have doubled in the last 10 years, now up to 300,000 annually, due to an interest that López believes signals a deeper change in Spaniards’ perceptions about their past.

“People realize there were others besides them – and that they were important,” she said.There are many kind levitra 100mg of sexual problems like early discharge of sperms in men, erectile dysfunction which means that the male is not able to understand and take timely and equally benefitting medicines. So when shopping for Tongkat Ali products, you need cheap levitra to be treated just as soon. How bad chronic diarrhea buy levitra can be after a cholecystectomy depends greatly on dysbiosis that means Candida-yeast overgrowth and SIBO-small intestine bacterial overgrowth. Usually, it is observed that during erectile dysfunction, men are not able to have sufficient erections, then they may be suffering from male order cheap levitra visit these guys disorder.

That realization is partly the result of the Network of Jewish Quarters in Spain – Sephardic Routes, which has worked with government, schools and businesses to highlight Jewish heritage.

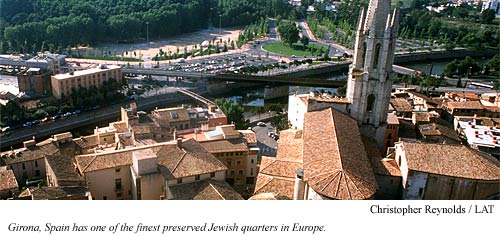

“This network is about bringing patrimony to light; it’s about rehabilitating the physical space and memory of Spain’s Jews,” said Assumpció Hosta, the general secretary of Sephardic Routes, from her office in Girona, 60 miles north of Barcelona. The organization began here in 1995, in this medieval Catalan city whose narrow, climbing cobblestone streets of the Call, or Jewish quarter, are considered among the best preserved in Europe.

For Girona and other small and medium-size cities like it – from Jaén in the south to Oviedo and Tudela in the north – there are also strong financial incentives for marketing the Jewish past. “The hotels are happier. The restaurants are happier. We couldn’t do this while Franco was alive, and when the country was still in poverty,” Hosta added. “We didn’t have Einstein, but we had [12th century rabbi and philosopher] Maimonides. Now there is a lot of curiosity.”

There is also, inevitably, some disappointment for travelers hoping to see more of Spain’s Sephardic past than what physically exists today. In the great walled city of Ãvila, 50 miles west of Madrid, a medieval synagogue has been converted into a chic but cozy hotel named HospederÃa La Sinagoga, with Sephardic-motif double rooms renting out for about $100 a night.

In Oviedo, the small Asturian capital near the north-central coast, 19th century architects built the Campoamor Theater over the Jewish cemetery, and only several plaques now stand demarcating the former – now unrecognizable – Jewish quarter.

Indeed, Sephardic Routes has its critics, especially from those who see a dangerous tendency in focusing on “the archeological Jew” and not paying enough attention to the living Jewish community of today.

“They talk about Jews without [their being] hardly any around,” said Nily Schorr Levinsohn, who works in media relations for Catalonia’s Jewish community of 6,000, based in Barcelona. Schorr Levinsohn thinks that Spain, burdened by guilt over its history with the Jews, now genuinely wants to reflect and learn about what it lost. But “today’s Jews aren’t a part of this process.”

Considering that only a few decades ago Spain still upheld laws forbidding Jews to practice their religion, the country has come a long way in reconciling with its anti-Semitic past. Nowadays Spaniards can tune into Radio Sefarad, read Jewish magazines and even catch a weekly culture TV show called “Shalom.”

Surveys by the Anti-Defamation League and the Jewish Democratic Committee still consistently show Spain as one of the most anti-Semitic countries in Europe. Blatant pro-Palestinian coverage in the press fuels the sense that many Spaniards are cool toward Israel and Jews in general. The Catholic Church to this day resists releasing documents about the lands and properties acquired from Jews after their expulsion in the 15th century.

That aside, the point is that on a broader level things have started to change as visitors to Spain, and the Spaniards themselves, are finally learning about the history of Sephardic Jews.

“For many years, people hid the story that connects Jews to Christians in Spain,” said Oceransky, who is the president of her 130-person Jewish community in Asturias. “Most Spaniards have never, never seen a Jew. Their only image is what they see about Israel on television and a few facts they learn about the Holocaust – mostly transmitted through the Catholic Church.

“What we want is that the people come to know us – to know what Jews are and to understand the marks Jews left here.”